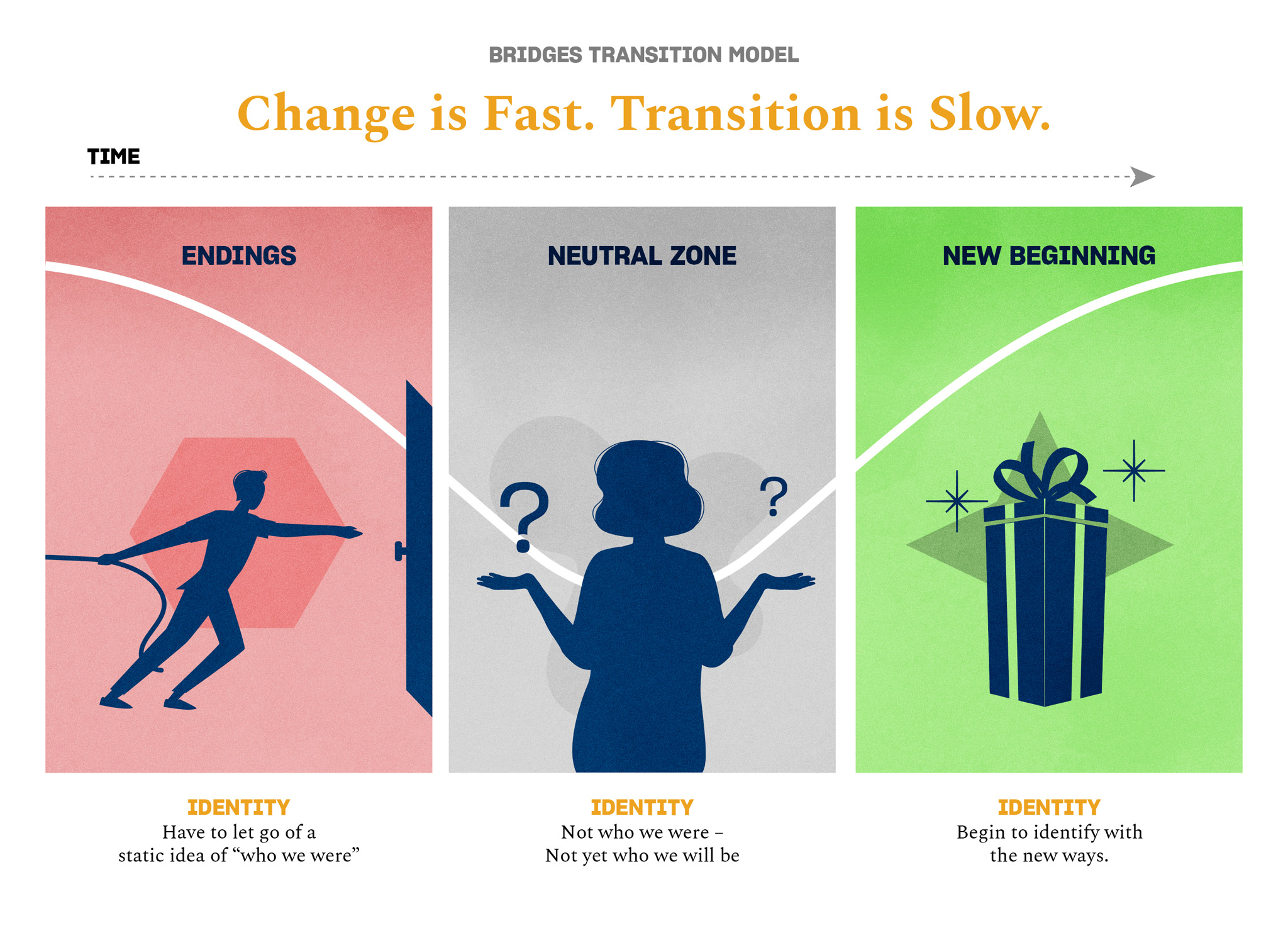

Change involves letting go of the past and creating something new or different. This process is not always straight forward or easy.

William Bridges, author of Managing Transitions, calls change a shift in your situation. It’s an event that happens quickly, followed by a much slower transition phase. If change is an event, transition is a process. Bridges defines transition as “the psychological reorientation you make to come to terms with the change.”

Specifically, we go through three distinct phases during a change. We start with the change itself, which effectively ends what used to be. This is the fast part. Next, we enter a slower transition, the “neutral phase.” Here we might process difficult questions, experience doubts, or face fears about the future.

ENDINGS:

Endings can be positive or challenging. A positive ending might be landing a new job. The opposite is being fired. Both scenarios begin with the end of what used to be (the old job), pass through the “neutral zone, and result in a new beginning. During the ending phase, you process letting go of the past. People tend to feel either optimistic and excited about endings, or fearful and worried about how the change will affect them in the short- and long- term.

NEUTRAL ZONE:

Even if we are excited about our upcoming job (new beginning), we pass through the “neutral zone” phase where doubts, questions, and fears about the unknown tend to show up. People often feel they are “in limbo,” experiencing “free-floating anxiety” before the new beginning has solidified. Challenging questions like, “How will I fit into the new culture?” or “How will I get along with my team mates?” characterize the neutral zone phase of positive change. We may even ponder whether we made the right choice or if we should have stayed put. If we didn’t initiate the change (we were fired), we may find the neutral zone challenging. Questions like, “Will I ever find a job I like again?” or “Will I have enough money to survive until I find a new job?” emerge, and we may question our skills, talents, and life choices. The neutral zone is, however, not all bad. It’s actually a powerful place to be present to the moment versus focusing on the past or future. In truth, that is all we actually have anyway. Two recommended key resources include The Power of Now and It Takes What It Takes. While one has a spiritual focus and the other based in sports psychology, they both apply to how we choose to view the space in-between “no longer” and “not yet.”

NEW BEGINNINGS:

Once people have passed through the neutral zone, and see “the end of the tunnel,” their new beginning or future becomes clear. In this phase we experience optimism, creativity, and innovation. If managed effectively, the change builds trust, provides transparency, and assures people that future changes may result in positive new outcomes.

When we are charged with managing and leading change, we have a responsibility to guide and coach team members through these phases as gracefully as possible. These steps will help you prepare to execute change with style.

PREPARING TO MANAGE AND LEAD CHANGE

Step 1: Review your natural response to change and recognize that everyone handles change differently.

Each person has a unique natural reaction to change. If you are familiar with your DISC behavioral style, apply that knowledge here. If not, read each DISC description below and select the style that resonates the most. For example, some people love and embrace change (and tend to be high in Dominance and Influence). Others are more reluctant or resistant to change (Steadiness and Compliance).

Dominant people welcome and love change. They quickly “accept and move on,” focusing on how to benefit from the change. The absence of change tends to make them “antsy,” so they might initiate change to get their creative sparks flying. They can get frustrated or annoyed at people who either require time to process change or don’t immediately embrace it as the “new normal.”

People high in Influence also embrace change, focusing, on its positives. Excited about new beginnings, they envision possibilities and opportunities. They tend, however, to “rush through” the neutral phase. This can result in a flurry of challenging thoughts and emotions once the new beginning is in place. They tend to champion change, hoping others will view it as positively as they do.

People high in Steadiness tend to have the most difficulty embracing change (especially if it’s unplanned). It’s not that they resist change per se. What they need is a clear step-by-step plan for how to manage and process the change. They tend to stay in the neutral phase longer and may resist a new beginning (even if it’s positive). They need reassurance and guarantees to buy into change. If handled well, however, they can become great supporters of the change.

For those high in Compliance, change will be embraced if it’s deliberately explained, makes logical sense, and connects to a bigger purpose or strategic initiative. Change for the sake of change (or impulsive changes lacking thought or deliberation) annoys this style, making it hard to get buy-in. As with the Steadiness style, people high in Compliance tend to stay longer in the neutral zone, requiring plenty of time before embracing a new beginning.

When leading and managing change, it’s imperative to acknowledge that each person (and style) embraces change differently. If you are leading a team, it’s safe to assume it embodies an almost-equal breakdown of the four styles, each with different needs and experiences. What seems like a small change to you, may be enormous to someone else.

Step 2: Slow down and remember, “change is fast, transition is slow.”

Most leaders are privy to major organizational change long before sharing it with the team. You’ve had a chance to process the impact, details, and outcome for a while. The moment you share the news, your team needs to pass through the three stages of change. Many leaders make the mistake of assuming that, as soon as the change has been announced, everyone will embrace it immediately. This is when you need to remind yourself that “change is fast; transition is slow.” Give your team members time to process. Coach them through the neutral zone and the natural transition that is bound to take place. Ask how the change affects them, and look for their natural responses to change.

Step 3: Review the impact of the change holistically (practice “do no harm”).

Before announcing or launching major changes, review how the change will impact the organization or team as a whole. Doctors take the “Hippocratic Oath,” vowing to “do no harm.” Leaders and manager must consider how change initiatives can do as little harm as possible. If it’s critical, communicate how the change will help “heal” the organization and lead to a healthier future. If your team believes you’ve considered all aspects of the change, they are more likely to buy in.

Step 4: Create and flawlessly execute a change communication plan.

While half the team might embrace and enjoy change, the other half might fear it. Prior to the launch of a major change, create a change communication plan including a carefully crafted announcement. Explain the reasons for the change and, offer a positive inspiring vision of the future (new beginning). Avoid “overselling” the positive aspects of change, as this makes skeptical people feel they are forced to support the new change quickly, with no time to get there on their own. Once launched, let them know you will follow up consistently (every week for X number of weeks), providing updates and check-ins. Transparency and consistent communication will help even the most resistant team members move through the neutral zone with grace.

Once your change plan is in place, it’s time to consider several key factors. Refer to these often as you manage and lead change.

KEY CONSIDERATIONS FOR MANAGING AND LEADING THE PHASES OF CHANGE

- Committing to change is a personal choice. Without a commitment to release the old, nothing new can flourish. Consider how you can encourage others to make personal commitments to change. If you don’t have support or positive forward movement, there’s probably a lack of commitment. Revisit the feelings, emotions, behaviors, and attitudes of the team. Uncover what they need to leave behind in order to embrace what’s new.

- We change for two reasons: Increased pleasure and decreased pain. Sometimes holding onto the old or refusing to embrace change must become painful before we move into action. As managers and leaders, we must clearly share the “pain” of holding on to the old. For example, if we refuse to grow, we may be passed over for promotion. If we opt to change, we may experience unlimited career opportunities. While decreased pain is a powerful motivator, increased pleasure sustains us longer.

- Clearly articulate how change connects to company strategy. Once people have a clear sense of why change is important and how it connects to big-picture strategy, they are more likely to embrace it.

- Get them involved! Most people feel more “in control” when playing a role in the successful execution of a change. Get them involved. Ask for their support. If you’re moving to a new office space, ask team members to help organize an “office warming party.” The more they feel part of the change, the faster they will move through the neutral zone in support of the change.

- Set up coaching sessions to sort perceived vs. real losses. Ending something (even when change is positive) often triggers a sense of loss. If not addressed or managed well, people may overemphasize what was lost instead of focusing on what is gained. They may overreact to issues that a quick conversation can resolve. Set up pulse-check coaching sessions early in the change phase.

- Let people talk. Some will need to vent and share their feelings. Others may disconnect or detach, signs they are processing their emotions internally. Take time to ask open-ended questions and listen to how the changes affect them. Do not judge. Each person responds to change differently. What may seem like an insignificant change to you may feel overwhelming to someone else. Most people just want their feelings acknowledged and voices heard.

- Acknowledge, Accept, and Move on (AAM) when the time is right. If you have managed the change well, there will come a time when you need to practice some tough love and let the team know “what isn’t anymore.” Holding on to the past with statements like “We used to do it this way” or “We never used do handle it that way” is a destructive sign that people have not let go. To open the next door, you must close the previous one. Sometimes a clear “line in the sand” is the healthiest approach.

- Normalizing the neutral zone. Without the neutral zone, we would jump from change to change without the chance to fully process our thoughts and feelings. Let people know the neutral zone is part of the process along with the ending and beginning. This gives team members “permission” to process their feelings. Otherwise, destructive behaviors like passive-aggression, gossip, and detachment may rear their ugly heads following the new beginning.

It’s imperative to consider the phases of change and your natural responses. Focusing on others’ needs during periods of change allows you to manage gracefully, leading others.